Summary

The Late period is the last three hundred years of the culture era.

Art types are no longer connected to architecture as the main expression of a culture’s soul.

Painting (Greek Fresco, Western Oil Painting), begins fine art but can’t master the culture’s prime symbol.

Music/Sculpture finish off the art style of the Western and Greek world respectively as finished expressions.

Western art can be described as “Impressionist”/moving away from bodiliness

Greek art can be described as “plastic”/moving towards bodiliness

Why is the Greek world so closely associated with classical sculpture and the West so closely associated with baroque music? Music existed in the classical world and sculpture exists in the West, but they are never the focus of our cultural production in the same way as these respective titans of fine art.

We know from previous posts that these choice arts reflect the soul of a culture, but how they resulted in the sonatas of Corelli or Beethoven, or the freestanding sculpture of Phidias or Polykeitos, requires us to question how these arts were attaining towards their culture’s symbolism. This requires us to look at the second stage of a high culture: the Late period.

The Late period is a 300-year timeframe following the Springtime Early period, constituting the Summer (the first half) and Autumn (the second half) seasons of Spengler’s model. The turning point from Summer to Autumn sees the completion of the Absolute state-form and Puritan religious form, and equally it also sees the completion of a secularized set of art-forms that approximately express the culture’s soul in a group of fine arts. In the West, the Late period spans from 1500 to 1800 AD, in the Greek world, 650 to 350 BC, and in the Magian world, 500 to 800 AD. It is marked by a transition of historical change from the countryside to the cities as centres of focus and with it the closure of all the land-bound types of art, politics and religion.

This poses a few categorical problems considering academia doesn’t agree with this model of development, especially for art history. This was illustrated in our last post when we addressed that Spengler only counts the Quattrocento period as the true Renaissance, with the proto- and high- Renaissances being Byzantine-Gothic and early Baroque in his eyes. Spengler categorizes the 1500s as the first century of the Western late period as it marks several foundational shifts to be developed on by the later Baroque, which is typically categorized as spanning the 17th century and not the 16th. But “Baroque” is the name Spengler gives to the whole 300-year time-frame in contrast to the “Gothic” early period.

He also names the 300 years of the Greek late period “Ionic” in contrast to the “Doric” early period. This goes against the conventions of Greek art history as well. Beginning in the 18th century with Winckelman’s History of the Art of Antiquity (1764) and continuing to be refined upon by 19th century classicists like Karl Otfried Muller, Greek art history is divided into an “Archaic” (c. 700 – 480 BC), “Classical” (c. 480 – 323 BC) and “Hellenistic” (c.323 – 31 BCE) trio of periods. There are more before and after but these cover the territory of Spengler’s late period. The Archaic is meant to highlight an era of “stiff” sculpture, the Classical, an idealistic “High style” and the Hellenistic, a superfluous breakdown in simplicity in attaining a degree of realism.

The Faustian and Apollinian cultures are the object of most of Spengler’s contrasts for his coverage of the late period as Spengler tries to drive a wedge, starting with the Renaissance, between the two cultures, making his case that they are not the same continuous heritage, but two separate swells in history whose characters couldn’t be more mutually opposed.

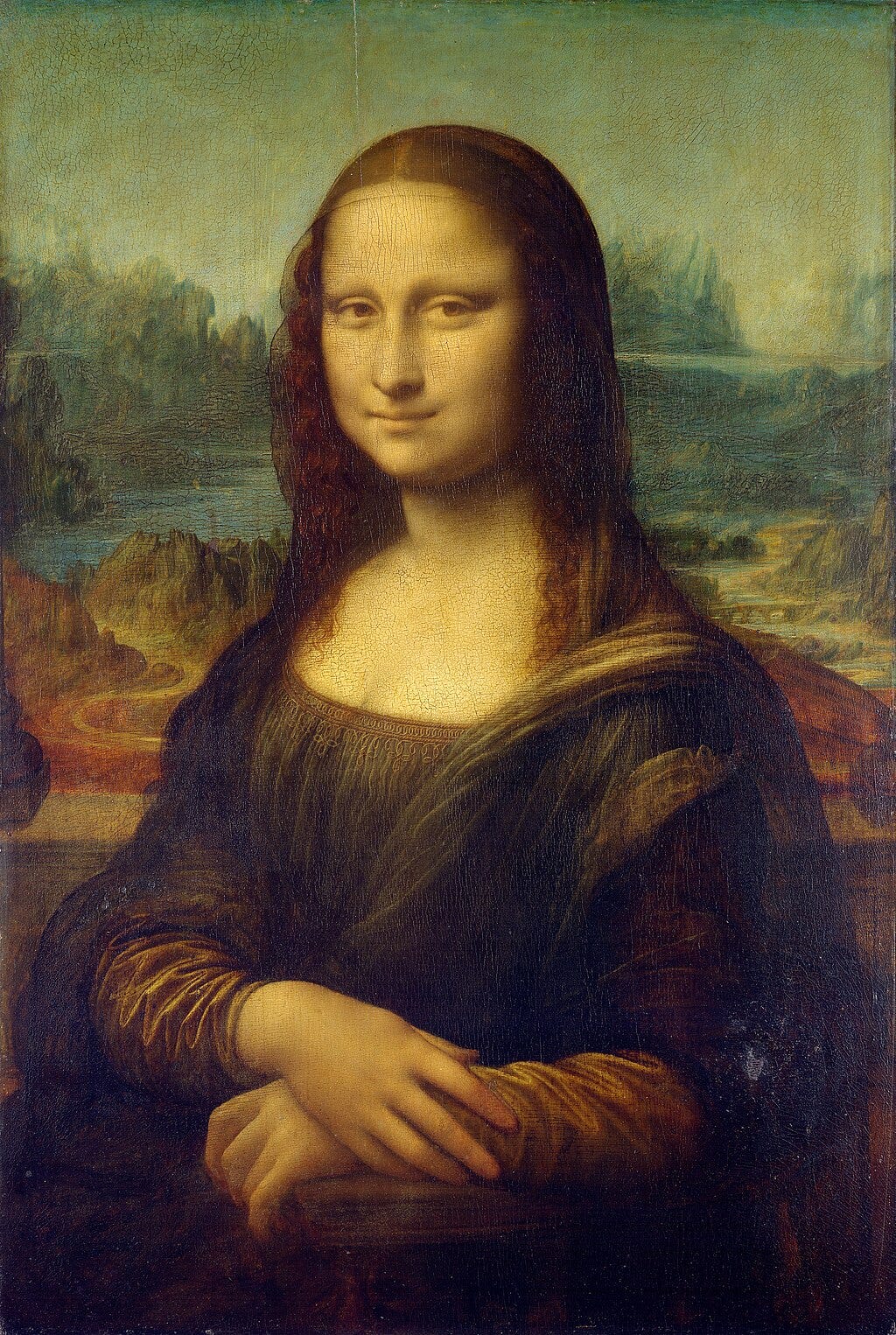

With the beginning of the Late period, architecture ceases to be the main form of expression for the great style. The Early period was a steady movement of Ornamental art from the 3-dimensional logic of building to intricate decoration, which resulted in an assortment of fine arts being selected to express the same ideas. In the late period, decoration breaks free from its relation to the decorated and becomes a pursuit of its own. This break can be seen at the end of the Renaissance. Fresco (Tr. Fresh) painting is produced by mixing pigmented powder with water on wet plaster. It is therefore just another decorative Ornament seen best in holy structures like the Sistine Chapel (above). Nearing 1500, however, you get a shift towards oil painting. There are practical reasons for this, to paint on canvas means it is easier to transport, but to paint oils on a canvas also liberates the decoration from architecture and makes it its own object of study.

The year 1517 also brought us the Protestant Reformation in the north. Martin Luther, unlike reformers of the past, was an urban monk and his mind was shaped by the sensibilities of dense alleyways and cobbled streets. The act of severing the need for a priest as a divine mediator between man and God indebted the individual protestant to understand the bible himself. This transformed the spiritual content of Europe overnight as suddenly the individual became big. The same transformation occurs in art. As arts grow into secular, or at least intellectual, endeavours, the individual master replaces the anonymous school.

The Mona Lisa has already been observed to display a novel tendency for its time. The painting appears to almost blend into itself. It experiments with dynamic shading and the background is not the linear perspective of the Renaissance, which, designed by Brunelleschi, is associated with architecture and not fine art, but is an illusive aerial perspective created by different colours thrown on chaotically with visible brush strokes and hazy forms which gather to create a something only when it is viewed as a whole and not for its fine details. In the Renaissance, objects were treated with their own individual actuality and paintings came together as an aggregate of forms that are readily perceivable on their own. With the rise of oil painting in the 16th century, this idea changes. Its another spiritual shift, this time away from rebellion and towards embrace of Faustian symbolism. Paintings can only begin to be perceived as a whole and not for their separate parts. This technique Spengler elects to call “Impressionism”.

“The effect that is made upon us by things that receive and reflect light is made not because the things are there but as though they “in themselves” are not there. The things are not even bodies, but light-resistances in space, and their illusive density is to be unmasked by the brus-stroke. What is received and rendered is the impression of such resistances, which are tacitly evaluated as simple functions of a transcendent extension. The artist’s inner eye penetrates the body, breaks the spell of its material bounding surfaces and sacrifices it to the majesty of Space.”1

Impressionism is a word assigned to a specific movement of the 19th century involving “visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, unusual visual angles, and inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience.”2 Spengler argues that the time frame assigned to such a definition is far too narrow, and works as far back as Da Vinci can be identified with the title; Impressionism is not an incidental fad of early modern art, but is a term descriptive of the very soul of Western art - painting and music. Impressionism is a symbol of the Faustian worldview that perceives the world as energy refined into mass, and we see this idea continued throughout its style.

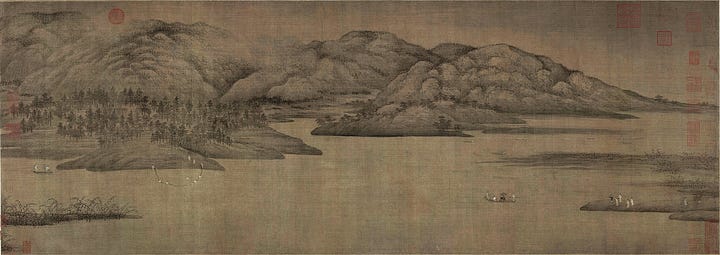

A symbol within impressionism that makes itself manifest in oil painting is the Horizon. It’s an element of our art that doesn’t exist in any other culture. Egyptian art rejected the third dimension by establishing superimposed ranks on their wall art. The Greeks created groups of bodies with a complete disregard for the background which was left bare. Byzantine imagery blocks off the background with the golden presence of the holy ghost and approximations by Chinese nature paintings, even giving them an additional two thousand years of leniency after their culture came to a close, is flat, creating depth purely through air effects. The Western horizon becomes a symbolizes the bringing of the infinitesimal idea into painting as linear perspective did.

Oil painting’s strength was that it was very slow to dry. This allowed painters to mix their colours very well and put painstaking time into refining every detail of it. The landscape paintings of the late period differ from renaissance paintings in that they begin with the background instead of the foreground. The artist begins with the underpaint, then applies layers, blends them, edits and mixes them, and applies details in relation to its proximity to the foreground. Titian’s The Rape of Europa displays this tendency well. The mountains in the distance bleed into the sky where we can imagine they were brought out of in successive blending and detailing. Horizons are symbols of the far distance for which we have yearned to cross and overcome, be it the Norse breaching Russia and Canada, Columbus attempting to sail to India across the Atlantic, Captain Cook discovering Australia or manifest destiny connecting the coasts of America by crossing the untamed wilderness. The cloud is also another Western symbol. It’s a form that is absent in Greek art because at its heart it is formless, floating in the heavens beyond our reach. Even without painting we recognise shapes within them and so they always appear within the horizon background far off in the distance as enormous mountains pluming into the sky.

In the early 16th century, painters continued the strong Renaissance colouring of blues, greens, reds and yellows. Even as light and dark were experimented on these colours persisted. In the latter half of the century, however, which particularly becomes apparent in painters of the Dutch golden age (c. mid-16th – 17th century), techniques like Chiaroscuro (dramatic light and shadow) and sfumato (soft transitions) began to employ brown tones as a base colour to evoke atmosphere and depth.

If we think about brown as a colour, its one that doesn’t exist on the rainbow. It’s an earthy colour that brings everything into itself as one homogenous shade and tone. Instead of sharp reds and yellows, you got yellowish and reddish shades of brown. This could be attributed to a simple incident of pigment mixes, but it should be considered that when the colour hadn’t been needed before, and suddenly appeared and popularised itself, that perhaps it expresses a tendency which aligns with the impressionism. That is, after all why it was employed.

Between the master of this brown colour, Rembrandt (c. 1606 – 1669), and a strong Catholic painter like Rubens (c. 1577 – 1640), we see a difference in how it is employed. The latter wields brown for shadow while his blues and greens remain dominant. The former lets his brown colour dominate every aspect of his painting. Spengler uses this to suggest that there is something Catholic about the already pervasive blues and greens of the south, and Protestant about the browns of the north. This ties the growth of art back to its connection with religion. Martin Luther’s Five Solae stripped all the colour and joy from the gothic world and created a purely intellectual environment for understanding God as a series of concepts without Mary worship or the Christian-European myths of the Middle Ages. Equally, brown strips the strong Renaissance and Venetian colours from the world in a grand reformation.

Impressionism doesn’t capture objects themselves, but the soul of the objects. Rembrandt’s self-portraits may be blurry but they capture the fine details of his emotions perfectly. A landscape painting treats the world-around as light and light-resistance, energy refined into hazy masses. Within the great arch of the cloister window, there are many smaller arches contained within. Oil Painting continues this premise. Of course, what is suggested by an image is only an illusion and at the same time as Oil painting came to a height, Music also accomplished the same tendencies in lock-step. Music had been around since the beginning of the West in a variety of ways and we will explore them now. We may be covering the late period, but it will be useful to cover it here at once.

Perotin - Viderunt Omnes (c. 1200)

In the early period, there was Ornamental and Imitative music as there was architecture. Ornamental music was the music of the Cathedral. It predominantly came out in choir song. Counterpoint, the relationship of two simultaneous musical lines playing at once, was invented at the same time as the flying buttress. Listen to Perotin’s “Viderunt omnes” or “Justus ut palma”. These voices echoing against the enormous open spaces inside cathedrals created unique effects simulating continuous sound.

Walther von der Vogelweide - Under der Linden (c. 1200)

The imitative music of the castles and villages was more folkish than religious. It was simpler, melodic and told secular tales of daily life. Take a listen to the French Troubadour “A Chantar”, the Spanish Cantigas de Santa Maria, or the German Minnesang (tr. “Love song”) “Under der linden”. By ear alone we can tell there is something irreligious and secular about them. They are sung poetry like the heroic tales of the Iliad or the Odyssey and not the self-aware and meaningful polyphonic chants of the cathedral halls. This motive carried on into the cathedral of Florence. Guillaume Dufay’s Motet "Nuper rosarum flores" (1436) maintained polyphonic voice’s supremacy under the dome.

Palestrina - Sicut cervus (c. 1604)

Music after this age would pass into the hands of the Italian city-states such as Rome and Venice, and come to be dominated by select masters of the craft. Beforehand, music was produced my pious participants, but around 1560, with the a cappella style of Palestrina and Orlando di Lasso, this style came to a close and music began to become more instrumental. This occurred because vocals alone could not properly express the wide range of sounds music ought to have been attaining to, like if a painter only used shades of black and white to create his painting. Its fine, suggestive even, but limited in a culture that seeks to transcend limitations. The early Baroque musician sees vocals as one among many pigments to paint his song.

Viadana - Cento concerti ecclesiastici (c. late 16th to early 17th century)

There came “Fundamental” instruments, such as the organ, harpsichord and cello, which provide a continuous tone throughout the music called “basso continuo”, and “Ornamental” instruments such as violins, cornettos and flutes which give us melody. Take a listen to Viadana’s “concerti ecclesiastici”. Your underpaint is the basso continuo of the trombones, then brushed on is a polyphony of melodies through the Violin and Cornetto. I used to believe classical music was quite chaotic because of this perceived incoherence of tunes, but what was being attained, to my lack of knowledge, was an impressionism of sound, and what was achieved in oil painting was being accomplished in succession with a less illusionary and more actual embodiment of infinite space.

Henry Purcell - Britain, Thou Now Art Great, Art Great Indeed! (c. 17th century)

The movement playing out here is a movement away from the bodiliness of vocal sound. The golden era of this was the Gothic period. The 1500s continued this until it reached the limits of its scope. Then you have a wave of musicians such as Henry Purcell (c. 1659 – 1695), Carissimi (c. 1605 – 1674), and Heinrich Schutz (c. 1585 – 1672) who mix both vocal and instrument, and upon their deaths in the latter half of the 1600s you have the succession of “pure music”. The fugues of Bach, the Sonatas of Corelli. The voices of the cathedral are extinguished and with it the input of the body. At the same time, the great masters of oil painting die off. Velázquez in 1660, Poussin in 1665, Frans Hals in 1666, Rembrandt in 1669, Vermeer in 1675, Murillo, Ruysdael and Claude Lorrain in 1682, they all perish. Purcell’s work can be argued to be “pictorial” in nature due to the indiscriminate use of his pallete of sounds. It comes at the inauguration of the age of religious Puritanism, and absolute monarchy in France. 1650 begins this shift towards the finalization of culture as a whole and art shows the symptoms of this maturity.

“Be the artist painter or musician, his art consists in creating with a few strokes or spots or tones an image of inexhaustible content, a microcosm made for the eyes or ears of Faustian man; that is, in laying the actuality of infinite space under enchantment by fleeting and incorporeal indications of something objective which, so to say, forces that actuality to become phenomenal.”3

Seikilos Epitaph (c. 200 BC)

In the West, relational harmony was the focus of our music. Keynote “A” sounds soft and warm next to the chord C E G, it sounds stable, strong and important next to F A C, it feels supportive next to D F A, and dissonant next to E G# B. As a result, it is important how one note blends with another, as the meaning of a note is defined in relation to all the other notes. Greek music has no conception of this. Against a polyphony of sounds, Greek music was, for the most part, single-voiced. Harmony was not its objective, and so “A” meant A irrespective of what chord it was with. The proportions, or ratios, of its tetrachords were what mattered and defined its meaning. When we consider that Greek music is partaking in an artistic direction towards bodiliness and not away from it like Baroque music, it makes sense why notes aren’t relational and tetrachords are measured by proportion. It’s closer in form to contemporary sculpture than Purcell or Mozart.

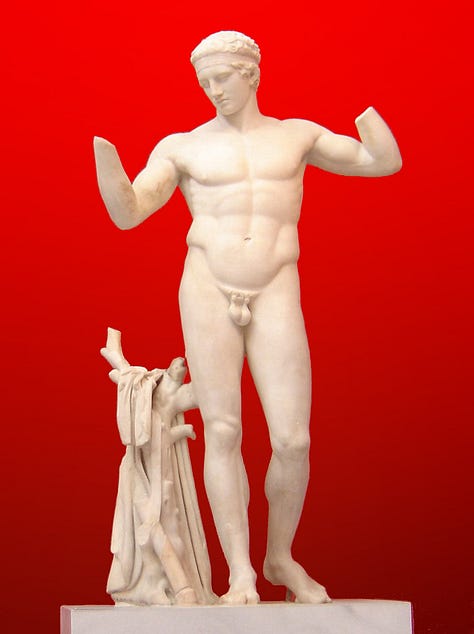

To move towards bodiliness is to move towards detachment, to round oneself off from your surroundings and have definitude of shape which is the ultimate antithesis of Western impressionism. It culminates in classical sculpture, which, if we follow the taught history of the art, hails from Egyptian statues before being made more dynamic and realistic in posture, but as an art form it hails from the fresco wall painting.

In 650, the Greek “Ionic” late period began, and around this time, we see the erection of the first stone temples. Fresco painting was largely an anonymous tradition up until Polygnotus. These frescos usually consisted of groups and scenes depicted without depth and, with Polygnotus, the last of the great painters, a tetracolour scheme consisting of blacks, whites, reds and yellows. Up until this last great master in 460 BC, even his contemporary sculptors like Myron were fundamentally bound by this fresco style. Temple pediments effectively display 3-dimensional frescos as sculptures were put in groups on the front. With Polykleitos, sculpture finally liberates itself from the back wall and becomes free-standing. Although sculpture was free standing beforehand, Spengler considers Archaic kouroi to not be of the grand style until the mid-5th century; just as oil painting passed the torch to music between 1650 and 1700, leaving a century of autumn dominance for orchestra, fresco passes the torch in the last hundred years of the late period (450 – 350 BC).

Beethoven - Symphony No.7 in A major op.92 - II, Allegretto (c. 1811–1812)

Lastly, this brings us to the final century of the late period. This is the solid autumn of a culture’s lifespan. After Polykleitos and Bach a host of successor masters, some well-known, some not, inherit the art-form and continue to master it. Phidias, Pasonius, Alcamenes, Scopas, Praxiteles, Lyssipus; Gluck, Stamitz, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. They continue to refine their arts to perfection as they near Alexander and Napoleon’s conquests of the known world. Architecture finished off with the Rococo style, “choked”, in Spengler’s words, in music. Though it is an architecture, it is so richly decorated that the simplicity of meaning in the Romanesque period is completely forgotten, and it’s any wonder why it became a contemptible style for 19th century. “They are sonatas, minuets, madrigals in stone, chamber-music in stucco, marble, ivory and fine woods, cantilene of volutes and cartouches, cadences of fliers and copings”4; Rococo architecture is closer to music than a castle or a cathedral, for that is the art that the West has attained to as the ultimate expression of its yearning for infinite space.

So now that brings us to a close on our analysis of cultural art. There is always room for more exploration but fundamentally we’ve learned that the West has always pushed its art forwards in relation to the goal of resonating with infinite space, be it the impressionist physics of a landscape painting or the underpaint of the basso continuo in baroque music, and the Greeks have always pushed towards increased bodiliness, detachment, rounding off, which our Renaissance saw as worthy of crude imitation, but never mastering the idea behind it.

The next post will cover civilisation and art. It may be a shorter post as Spengler occupied himself with the culture period for the most part, but it can definitely be extended as we take a look at art closer to today.

The Decline of the West Volume 1, pp.285-286.

The Decline of the West Volume 1, p.286

The Decline of the West Volume 1, p.285