Summary

The Renaissance is not a “revival” of Classical culture

It is a product of geography, imitation, gothic symbolism, emerging art-types, and above all conscious rebellion against gothic motives

Despite attempts to be a counter movement to gothic music, Faustian tendencies still emerge through the cracks of every piece of art in this period.

The Renaissance consists purely of the 1400s. Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo coronate the beginning of the Late period and the Renaissance dies with them, which goes against academic consensus.

In the previous post, we explored how architecture expresses in one motion the whole great style of a culture through early architecture as it comes to a height in the early period. Holy architecture is built entirely for itself and becomes a representation of a culture’s prime symbol through 3-dimensional logic displayed in stone. The West in particular went from lacking a sense for itself in the Carolingian period, to, at once, gaining an identity made manifest through Ottonian and Romanesque cathedral architecture, before steadily assuming a high-gothic character marked by heavy decoration. The absoluteness of architecture giving way to decorative elements is as though microcosms are forming within it to explore particular ideas more vaguely addressed by the macrocosm. The Renaissance period (the Quattrocento1 will be our main focus), continues on this movement by challenging the West’s understanding of these secondary art-types.

The Renaissance, as the average person receives it, is the revival of humanist values and culture after the vicious medieval dark ages terminated the Roman empire with Christianity and barbarism in Europe. This is also asserted by historians like Vasari and Burkhardt. The “before times” were marked by guilds, serfdom and oppression and the Renaissance blessed us with a wave of creative personalities that reinvigorated European culture for the best. Spengler opposes this with a more careful attitude. He proposes a multifaceted perspective on the Florentine2 Renaissance that makes it a product of factors like symbolic rebellion, geography, imitation, personal taste, and the budding of independent art-techniques before the arrival of the Baroque period. What he does not assert, however, is the standard view that the Renaissance – literally re + nascence, or rebirth – is the resurrection from a declined state of civilisation.

Section five of chapter seven is devoted to this stage of art history. It is almost singularly focused on our renaissance, but as he establishes the rules and definitions of his renaissance, we will see that every culture has one of their own, not as a revival, but as rebellion.

“The Art of the Renaissance, considered from this particular one of its many aspects, is a revolt against the spirit of the Faustian forest-music of counterpoint3, which at that time was preparing to vassalize the whole form-language of the Western Culture.”4

As the early period was reaching its finishing centuries, music had become the dominant expression of Faustian art in the West in distinction from other modes of artistic production. It is ethereal, bodiless, limitless, expansive, dynamic, instrumental and an integral expression of the Faustian soul, rendering it no surprise that it would have been inescapable in medieval Europe from bards to castle grounds, organs to choirs and psalms. It would have effortlessly become the only art form of the West without the Renaissance in the way of it which, like a teenager apprehending its future, was to kick up a fuss and rebel against this direction. This is the core motive behind the interest in classical culture. The opposite of music was expressed in the tradition of classical sculpture: a hardened instant in marble, stoic and silent and sturdy, it was the symbolic opponent of music and therefore of Faustian culture.

It’s important to address however that this rebellion chose the Classical culture as the nearest accessible means of expression to this end, and if another culture were available, say the Egyptian, the historically oriented Faustian culture, valuing depth in time, would have seized on components of Egyptian art as well if it could, as we will see it did with the Magian. Greece had its own Renaissance, which, according to Spengler lay in the Dionysiac movement, which opposed the Apollinian culture with explorations of ecstasy and passion, this desire to loosen oneself latched onto the Dionysus cult in Thrace, but the cult itself didn’t cause the feeling to emerge. The feeling simply needed something tangible to latch itself onto, and so the stern Apollinian spirit was opposed by the free-spirited and ecstatic cult of wine and passion represented by Dionysus.

Let it be known that the Renaissance existed inside of the Gothic (Early) Period. “Gothic” is simply the name of the timeframe for the Western early period and, just as there is a distinction between the Thracian cult of Dionysus and the Dionysiac movement, there is a distinction between the settled language of Gothic design and the actual feeling being expressed through symbolism. Divorcing the term Gothic from the pointed arch and flying buttress allows us to identify these tendencies in the south as well where the northern techniques didn’t take hold until later on. During the medieval period, Italy was dominated by Byzantine and Moorish5 art-languages and this continued into the Renaissance.

“Plenty of things in Spain give the impression of being “Classical” merely because they are Southern, and if a layman were confronted with the great cloister of S. Maria Novella or the facade of the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and asked to say if these were “Gothic” he would certainly guess wrong.”6

Here Spengler mentions the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. With its façade designed by Leon Battista Alberti, it is a perfect example of how a building’s Southern European appearance can be mistaken for not being Gothic in spirit. We just have to observe the design for leaks in symbolism, as what is imitated, such as the Moorish, Sienese, patterning, or consciously willed, such as the proportions borrowed from Vitruvius7 and blended with Alberti’s own ideals, gives way to the inevitable sensibilities of Gothic design. What’s resolutely unclassical on the surface is that the Corinthian columns are raised up above the ground. All classical temples have their columns firmly on the stylobate. Doric columns appear to almost bore into the ground, conjuring an absoluteness of stability. Here the Corinthian columns are raised above the eyeline on plinth blocks. Not only does it make these columns float above the ground, detached from it, but it also forces the viewer’s eyes upwards, just like a northern cathedral. It stands that here, in spite of a conscious rebellion underway against gothic architecture, this small detail is a leak.

Another more thorough example is the Pazzi Chapel by Filippo Brunelleschi. This time the columns are on the ground. The design seems to imitate the Forum of Constantine or other Syrian temple fronts. But what strikes out about the façade is, in fact, the façade itself. Middle Eastern buildings turn away from the street just as the interior is the focus of its decoration. The temples of the Classical world, seen in Italy at Paestum, show that these structures exist alone, detached and unrelated to their surroundings, like their statue, but the Western building announces to the street what its purpose is, many-windowed and proudly designed. The Pazzi chapel is approached along a straight path. You are told the function of the building before you even get close to it, and the façade has always been a powerful part of any northern house of God.

Then there is the crowning example. Brunelleschi’s Lantern dome atop Florence Cathedral. When Brunelleschi designed the dome, he resolved to have an inner and an outer dome supporting the weight of one another. The dome of the Pantheon was hemispherical, as were most domes up to that point, so it goes without saying that a glance at the Florence Dome shows it is pointed, distributing weight downwards more easily and creating a circular equivalent to the gothic pointed arch, but it also resonates with the musical idea of counterpoint, the voice of the inner dome supporting the voice of the outer and vice versa. The only problem with this is, as we’ve observed twice now, the Pantheon isn’t classical, its Magian.

“If we take away from the models of the Renaissance all elements that originated later than the Roman Imperial Age — that is to say, those belonging to the Magian form-world — nothing is left.”8

Renaissance men didn’t have a very critical eye for what was Classical, Imperial or Byzantine, as these distinctions are largely modern. As a result, many artifacts of what we would call Magian culture, belonging to the middle east, find their way into Renaissance structures. Many of the palaces of Florence contain open courtyards, these are Moorish in origin. The arcades are the arches bursting out of the capitals and not those of the Theatre of Marcellus or the Colosseum. These are thoroughly Magian and Islamic in nature and are seen all over Florence. Its evident then that despite the copied features, the spirit of the age permeates Florence, not as a radiation from up north, but as something readily available on Italian soil and ready to express itself as a solution to problems Florentine architects wish to ignore.

We are therefore faced with several dimensions to the Renaissance already. Firstly, we have a conscious resistance against, and unconscious failure to resist “gothic”, northern style. Secondly, we have an active pursuit of a perceived “classical” style through various elements taken from this dead style’s corpse such as writings and ruins. Thirdly, we have an unmistakable inability to purely revive this style due to imitated Byzantine and Islamic styles that have endured in the Tuscany region since before Faustian culture was even born, and a pervading sensibility in Gothic tendencies. We call this melting pot a “rebirth”.

What is actually occurring here though is simpler to understand. The various families of Florence, the Medici family in particular, who commissioned these works of architecture, sculpture, painting and so on, are pursuing their own personal tastes. There isn’t a clearly resolute logic behind it like Romanesque or early Gothic architecture. Once architecture gave way to decoration, and decoration began to be generally consumed by wealthy urban elites who hadn’t time to waste on disciplined form, personal taste began to seep into what was produced. This returns us to exploring various non-musical arts, now with the sentimental backing they needed to be produced.

Here we break from architecture as the grand mode of expression. It has attained to what it can and now it is left to the little styles to express the prime-symbol further.

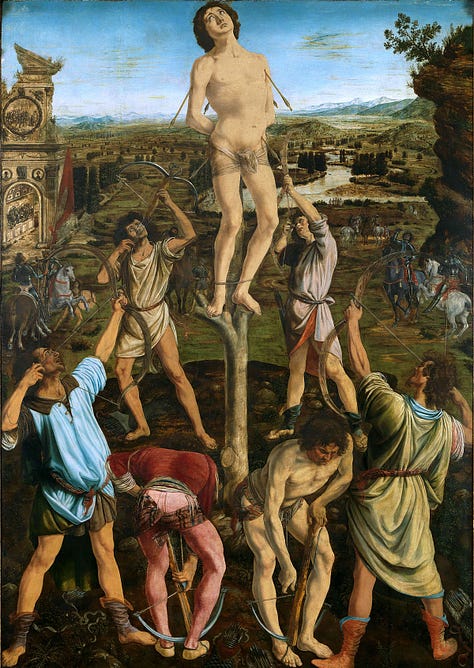

The fine art of oil painting had not reached its stride yet and wouldn’t do so until the Dutch golden age. In the Renaissance, the modes of artistic expression centred upon Fresco painting and sculpture as a pursuit of bodiliness. Above is Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ, Pollaiuolo’s Saint Sebastian, and Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. These paintings are stuck between desiring to manifest both Faustian and Apollinian types. On the one hand, the classical elements are visible in the lack of depth. the Botticelli is particularly poignant as the background has been stripped of any significance and renders flat whilst all the attention is placed on the foreground characters. Venus, just like Christ and Sebastian, are all rounded off from their surroundings, their lighting and shading draws them out from their backgrounds and rendered separate from it. This is exactly what we find on old Greek frescos. The background is neglected to focus on the posturing of the characters in the foreground.

Spengler also has much to say about the nature of Southern Europe and its impact on the kinds of paintings produced there. The sunny, bright daytime culture produced an almost shadeless atmosphere. This is best seen in Piero Della Francesca’s works. His Flagellation of Christ creates a bright, washed-out image consisting of various shapes overlayed to simulate depth. The attempt being made here is one of creating a scene that consists of a plurality of separate forms. The Faustian elements begin to seep through from here. A Polygnotus painting completely negates any and all background in the spirit of denying any and all space, but the Faustian still attempts to contextualise its figures within one. This century saw the innovation of linear perspective from Brunelleschi’s works. This development correlates to Cusanus developing the “infinitesimal” principle, deduced from the idea of God as Infinite Being. By Francesca’s time he was already capable of deploying this theory to create depth in his Flagellation, and suddenly space was given a content in the Renaissance it hadn’t had before, nor was it fully possessed by the Romans they sought to imitate. But even where it faded to a backdrop, in the pure fresco of the Greeks, backgrounds there were none, but however neglected during the Quattrocento, in the West they survived and then thrived.

We’ve already looked at the sculpture of the West, and in Florence it was no different. Indeed, sculpture was modelled, from the 1400s onwards, after Classical free-standing statue, but it was anything but freestanding. There is a parallel to be had here in the desire to capture the Classical spirit in the free and independent body, met with its contextualization within a background, in this case, the niche. For more reading on the differences of sculpture, I will cite Culture and Art.

Regarding boundaries to the Renaissance, Spengler differs greatly from the documentation of other historians and the general scholarly consensus today. Our best primary source for the history of the Renaissance is Vasari’s Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1550; revised in 1568). He subdivides the “Renaissance” into a trinity of periods: an “infancy” spanning the 13th and 14th centuries, an “adolescence”, spanning the 15th – the Quattrocento – and a “maturity” consisting of the High Renaissance of the 16th century. He did not use the word Renaissance, but recognised a revival of art after a steady decline culminating in the 1500s. That word “Renaissance” was popularized by Burkhardt in The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860) to describe the process as a single cultural movement towards individualism and secular life in this period. In Burkhardt’s time, Italian and German historians began to popularise this trinity model as the “Trecento”, “Quattrocento” and “Cinquecento”. In contrast, Spengler’s definition in 1918 purely resided in the Quattrocento, specifically going on from about 1420. From a footnote:

“It was not merely national-Italian (for that Italian Gothic was also): it was purely Florentine, and even within Florence the ideal of one class of society. That which is called Renaissance in the Trecento has its centre in Provence and particularly in the papal court at Avignon, and is nothing whatever but the southern type of chivalry, that which prevailed in Spain and Upper Italy and was so strongly influenced by the Moorish polite society of Spain and Sicily.”9

So here we see that this movement didn’t extend that far, but radiated its significance as though Florence Cathedral was indeed a Lantern.

The Trecento is associated with artists like Cimabue and Giotto. If we take a sample of their work, empirically they are continuing on existing traditions and techniques borrowed from Byzantine styles. The pervasive golden backgrounds of the Sienese School10, the noble Theotokos instead of the Mother of our Sorrows. There is hardly anything even European about their work, bar, of course, architectural tribute to the dominance of the Gothic. Even so, Italy in the “proto-Renaissance” period is influenced by other regions.

The Cinquecento, the “High Renaissance”, is, for Spengler, the first century of the Baroque (Late) period. If the 1500s gave the impression of continuing the Renaissance in any capacity, it is merely down to the continuing of traditions whilst gradually shaping it into something more appropriate with the sensible Faustian mean of music, departing steadily from its nature as a counter-movement. In this case, fresco gives way to oil canvas and oil canvas gives way to music. This is not to say they don’t exist in parallel, but over the course of the following three centuries, music affirms itself as the primary form of Western expression. The blocky and bright Quattrocento frescos with rigid foreground figures give way to extensive atmospheric landscapes full of dramatic scenery; painting becomes musical.

This may ring painfully in the ears of any Renaissance enjoyer, as it tears in half the three men the period is most known for: Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo. To account for this Spengler explores this trio extensively in section 4 of chapter 8:

“Each in his own fashion, each under his own tragic illusion, these three giants strove to be “Classical” in the Medicean sense; and yet it was they themselves who in one and another way — Raphael in respect of the line, Leonardo in respect of the surface, Michelangelo in respect of the body — shattered the dream. In them the misguided soul is finding its way back to its Faustian starting-points. What they intended was to substitute proportion for relation, drawing for light-and-air effect, Euclidean body for pure space. But neither they nor others of their time produced a Euclidean-static sculpture — for that was possible once only, in Athens.”11

Spengler’s attitude to these three “Renaissance men” was that they aimed for the Renaissance but, in trying to add to it, transcended it and inaugurated the great return to Faustian roots during the Late Period. Having looked at why this is, we are able to understand and reaffirm Spengler’s morphological assessment of the Renaissance and its limits.

The idea of the classical sculpture as the icon of the Renaissance was mastered by Michelangelo. Pieta, Moses and David are all masterpieces of the early-High Renaissance, and at such a young age as well! But as his life proceeded, his attitude to artistry brought his interest in marble to a close. To the Greek, marble is apeiron: the boundless chaos crying out for given shape and form. For Michelangelo, the marble is a prison to cut something free from. The Greek was purely focused on the shape of the exterior to create an act, but Michelangelo saw an inner spirituality to the marble that the Greeks refused to. Remember the Veiled Virgin! His David statue consists in the same idea of stretching skin over muscle over bone. David has a very clear facial expression which gives a soul to the marble that simply not a question for the Greek sculptor. In his later life, marble became a hindrance to the inner form Michelangelo sought to explore. His sculptures slowed down and lost their fineness as he shifted his focus to architecture. As he focused on architecture, the idea of music returned triumphant. A notable addition from him on the interior of St. Peter’s Basilica is the grouping of pilasters in pairs, pushed together to create niches for sculptures. The Piazza del Campidoglio he designed in an oval shape, creating a dynamic, resonating space in opposition to the hard square measure and proportionality of Roman-imitating Florence. In other words, by the end of Michelangelo’s life, he was departing from the Renaissance as a source for anything progressive.

Leonardo was thoroughly a discoverer and a scientist. The idea of discovery simply doesn’t sit right against the backdrop of Classical history. The discovery of interior anatomy and the circulation of the blood was by no stretch of the imagination a renaissance idea. It was a Faustian idea and therefore belonged to the Gothic world so berated by Renaissance historians. Leonardo is most well-known for the Mona Lisa. He painted a great deal in his life. But the Mona Lisa is striking not for the ambivalent smile but the technique employed to produce her. What we see here is an early stage of what Spengler calls “Impressionism” which comes to become the characteristic signature of Baroque oil painting. It is a departure from the certain boundaries between figures and forms in the previous century. It defies the established technique as the strength of the Renaissance as a movement fades.

Raphael embodies the last of this Renaissance outline before Leonardo inaugurates the Late period. The Sistine Madonna is, for Spengler the true culmination of the Renaissance spirit, thus ending the movement here. The lines that divided body from body, architecture from architecture, foreground and background, completely dissolve in this painting. Look closely at the cloudy background behind her and see the ghostly faces of unborn children. This airy image could not be produced with previous artists as it takes a certain mastery of impressionistic imagery to pull off. Within this image, there is no architecture, only purely boundless space with the icon of the age placed in the middle.

And these three figures transition us out of the Renaissance and out of the Early Period. They were masters of the Renaissance, but one foot was in and the other out, and any word about Renaissance men after them is ill-founded. We’ve seen now that the Renaissance wasn’t a revival but a southern tinted rebellion against the disembodying musical spirit of our Western culture. It came at a time when cities were about to become a political force to be reckoned with, but as yet dominated by wealthy families, many from Florence earning for themselves a taste in the 1400s for a certain kind of art that spiritually opposes music. This opened up the art stage to new techniques that didn’t necessarily have to honour the symbolism of its culture but could readily oppose it, resulting in improvements in fresco painting and sculpture. But, as we shall see, the three hundred years from 1500 to 1800, nay, even the first 150 of these years up until the coming of spiritual puritanism and the absolute state, see a correlative return to music as the dominant art form of the West, assuming that could ever be doubted.

The next post on art history will look at the Late Period.

Quattrocento – Simply Italian for the 1400s, Renaissance history typically correlates to century-based epochs.

Florence, Italy – The city where the Renaissance took place for the most part in the Quattrocento

Counterpoint is a relationship between two musical lines that share harmony. The relational interplay of two voices was a medieval innovation that became widely popular, we see it today on music sheets and simply accept its intuitiveness, but it is Western through and through.

The Decline of the West Volume 1, p.232.

Moors – Muslims of the Maghreb part of North Africa and, at the time, Al-Andalusia (Muslim occupied Spain)

The Decline of the West Volume 1, p.234.

Vitruvius – Author of “De Architectura” an Imperial Roman manual going into profuse detail on the rules and regulations of city construction and architectural design.

The Decline of the West Volume 1, p.235.

The Decline of the West Volume 1, p.233.

Sienese School – an art school in the city of Siena, borrowing heavily from Byzantine directives.

The Decline of the West Volume 1, p.274.