In this post we will explore some enlightening examples of how the spirit of a material art technique, particularly sculpture and architecture, not only differs radically between cultures, expressing wholly different feelings and attitudes about the world around, but also resonates with adjacent technical disciplines from their respective periods.

To recap the first post, art is, fundamentally, man’s departure from nature into technics. Art doesn’t constitute a specific set of material disciplines like painting, music, photography, and so on, rather, what we consider to be, and not to be, art, or fine art specifically, is an expression of our cultural mindset. The very notion of “expressing” something implies that it is momentary and personal, and cannot adhere to a timeline of development. As such, Rembrandt and Bach, as contemporaries, express not a history of portrait and music respectively, but mastered expression of the feeling of their era. If art is to have boundaries at all, they are historical and not material. Expression itself bubbles up from plain “imitation”, the act of mimicking, resonating, copying another, without any inner meaning to the action, to “ornament” something spiritually symbolic which expresses itself underneath the surface of a culture in all walks of life. When the spirit of expression is gone, all that remains of a piece of art, fine or not, is the external, explicit, visible side, no longer expression, simply a language of communication.

We can start by addressing what counts as “cultural”. What is Art established that fine arts are elected as an expression of a motif in a culture, but to keep that post on the shorter side I am only going to explain it properly here. Ornamental, culturally symbolic, art, within a higher culture, is what Spengler called the “great style”:

“The phenomenon of the great style, then, is an emanation from the essence of the Macrocosm, from the prime-symbol of a great culture. No one who can appreciate the connotation of the word sufficiently to see that it designates not a form-aggregate but a form-history, will try to align the fragmentary and chaotic art-utterances of primitive mankind with the comprehensive certainty of a style that consistently develops over centuries. Only the art of great Cultures, the art that has ceased to be only art and has begun to be an effective unit of expression and significance, possesses style.”1

Some of the more observant readers will notice that there’s a seeming contradiction in depicting art as technical, then going into the wishy washy and subjective forms it can manifest as; 1 plus 1 is 2, right? The opposition of discipline and form is integral to Spengler’s morphological theory of history. Where Spengler uses the phrase “prime-symbol”, he is referring to a culture’s characterisation of the world in relation to itself. It’s a definition for our connection to the rest of the world that informs all our cultural output. The West’s prime-symbol is infinite space. We conceive of reality as an infinite universe, with ourselves as increasingly irrelevant, arbitrary, and small parts of something that was here long before, and will be here long after, we were here. But that doesn’t go for all cultures. We will spend a great deal of time studying Greco-Roman art. The Apollinian prime-symbol is the Soma (body). Between 1100 BC and 350 BC, a culture resided in the Mediterranean that conceived of reality as a “kosmos” of interacting bodies, be it the atoms of Democritus, or the clashing pantheons of gods and titans. Distance wasn’t infinite, in fact all space outside of concrete forms was non-existent. The fact is, our technical outlook of the world is episodic and fundamentally characterised by a wide range of factors, the primary one being geography. The vast open plains and ancient forests of northern Europe created a culture that perceived far distances and timeframes, pulling us into them via traversal over land and ocean and extensive cultures of kinship, our veneration of the will-to-power birthed the science necessary to project the illusion of being able to objectively describe the universe. This cultural character has a strict duration and development over time, ending in the culture’s death and centuries long demise after the 1000-year mark.

Faustian culture, our culture, lasted from 900 – 1800 AD, Apollinian culture spanned from 1100 – 350 BC, Magian culture, in the middle east, spanned from the birth of Christ to around 800 AD, the Egyptian lasted from 2900 to 2000 BC and China lasted roughly from 1300 to 300 BC. These are the cultures we will focus on in this series, with special emphasis on the first three.

Outside of these higher cultures, with their historical boundaries and geographic territories, “prime-symbols” and “macrocosms” do not exist. Hunter-gatherers, in the ice age, painting on walls may conjure an iconic mental image, but it is not a style. It is not an expression of a higher conception of existence. Their hunter-gatherer lifestyle had a role to play in this. It was only when man began to settle on a landscape that the landscape could influence him as the first bit of permanence in his life. Prior to every higher culture, be it the Mycenaean period in Greece, the Aryan Invasion period in India, the Carolingian period in West Europe, we find people begin to settle down on the land as loose servitude is established towards lords who preside over it as the spoils of conquest.

But this is about art. The point is that higher cultures have a unique expression, this is a fleshing out of the previous post for this one’s sake. The idea of the Great Style is a clear refutation of the progressive narrative of history. “Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo are only stages of one and the same [great] style”2 within the constitution of the Western great style. Infinite space will be seen present throughout all these artistic periods. These episodes are preceded by an age where the desire for form is there but is still an imitated blend of a range of forms. “The Carolingian period stands “between-styles.” We see different forms touched on and explored, but nothing of inwardly necessary expression”3. After the grand style ends with the civilisation period. The inward form disappears and all is left is the external elements to give way to repetition and imitation once again.

It’s a very convincing theory in spite of its flaws. The famous graph from Murray’s Human Accomplishment comes to mind, where after the 1600s an explosion in human achievement sets in, suggesting the West’s exceptionalism or at least an exponential growth of human development. But do not be deceived, we are measuring ourselves by ourselves. An art example: Sculpture. A gander at Egyptian human sculpture and we see very chunky, vertically inclined, forward gazing statues. They’re literally all forward facing. The Archaic Greeks, inspired by Egyptian works, began creating Kouroi. Egyptian statues are to be looked on from the front, but the Greeks contributed a dynamic aspect to them: contrapposto, musculature, and most important of all, an emphasis on free-standing. Hellenistic and Roman sculpture improved on this until the dastardly Christians came along and destroyed them as affronts to God, resulting in a decline of statue as the Dark Ages set in. But then, the Renaissance revived the “art of statue” and introduced anatomical knowledge to further refine and improve the sculptures to life-like quality (except of course for the whiteness of the marble, which showcases a barbaric supremacism still lingering). It’s horseshit.

Lets look at Classical Sculpture. The opening to Chapter eight asserts that the Greek statue is not as intuitive as a presentation of the human form as we might think, largely due to the presence of different human presentations in other cultures.

“It is not true that this language of the outer surface is the completest, or the most natural, or even the most obvious mode of representing the human being. Quite the contrary. If the Renaissance, with its ardent theory and its immense misconception of its own tendency, had not continued to dominate our judgment — long after the plastic art itself had become entirely alien to our inner soul — we should not have waited till to-day to observe this distinctive character of the Attic style. No Egyptian or Chinese sculptor ever dreamed of using external anatomy to express his meaning.”4

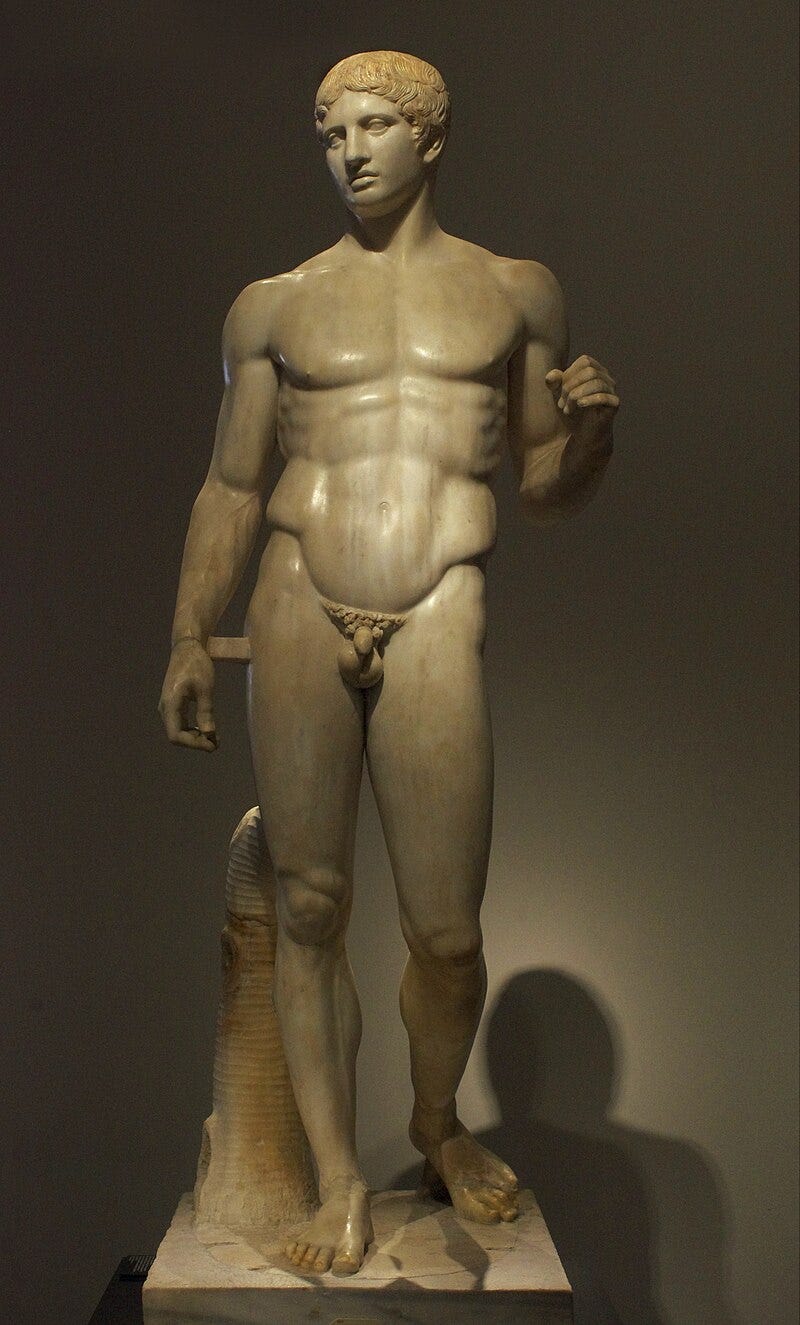

Above is the Doryphoros. This marble spear-holder is a Roman replica of the original Polykleitos Bronze cast from 440 BC, but we can reasonably trust it is faithful to the original and serves our purposes regardless. We’ve briefly observed that the Greek worldview is premised on the body, so sculpture’s prominence in Hellenic art is a given. But more importantly, the statue is fully nude. While the West affirms space, the Greek denies it in all its forms and that includes clothing as something extensional. The nude human body was a symbol of male, and sometimes female, virtue, but as ornament, the nude asserted a form without any extension. We can tie this idea to Greek philosophy. Parmenides’ Monism5 became a challenge to be addressed by every Greek philosopher since. His denial of “what is not” resonates with the Greek ideal of nudity. The nude is typically seen as symbolic of aristocratic virtues, the phrase “kalos kagathos” means “beautiful [and] good” suggesting a completeness of moral character which the male nude symbolizes in needing nothing else to compliment him. But it also extends to later ethical treatises such as stoicism, the denial of what you cannot control rounds oneself off from the world, detaching from it all in the pursuit of freedom and discipline. We could go on, but they all have a spiritual element of nudity in them.

Despite the emphasis on the nude body. If you take a closer look, you’ll realise it isn’t anatomically accurate. Not one Greek statue is. Galen applauded it for its exceptional proportioning, but the work on the statue remains purely surface level. This goes neatly with the stoic facial expression. Archaic statues had a distinctive smile, but classical statues are purely emotionless in expression. What this signifies is that there is no consideration for the interior, and certainly not the interior’s relationship with the exterior. The dynamism of emotion cedes self-control to the world both outside and in, both of which are denied to attain the perfect human form. The nude, the absence of interior, physically or emotionally, the free-standing contrapposto, these are quite typical for most Greek statues. Did not one sculpture try something different? We’ll never know for absolute certain, but the attempts of even many wouldn’t disprove the rule6.

The West, with its contrasting view, wasn’t so averse to clothing or self-expression. Just from a general standpoint, clothing has always been a form of expression for the soul in the West, be it the drapery of saints on cathedrals, the excessive fashion of wigs, coats, buckled shoes and lace cuffs which dominated the Baroque and Rococo, the military vest or the business suit. Though it’s understood that the nude is dirty and sexual, this is more a justification for a different sentiment, clothing tells us the nature of the person and their function.

If we look at the sculptures of Orsanmichele, Florence (above), or the royal portal of Chartres cathedral (above), we can see these statues are at best only theoretically freestanding. In reality these works are part of the architecture itself, embedded in niches against the walls or in the columns themselves. This detail symbolises something different: the integration of mankind into the grand tapestry of creation. Classical and Archaic sculpture represented ideal male types and not particular persons, but Western sculptures are of very real people, faithfully depicted or not, human beings torn between good and evil, perfection and chaos, space and matter, confessions of an entire inner world of mortal desire, emotional conflict and socially willed character, that Classical art refused to explore. Accompanying Western sculpture therefore is the art of autobiography, an urban contrition for the Western soul to be heard. Strazza’s Veiled Virgin (below) masterfully depicts a tendency that would be mistaken for simple anatomical accuracy, which is our ability to make the exterior a function of the interior. Our whole mathematics is premised on this tendency of y = f(x), but it finds its roots also in the cathedral style, the enormous interior is held up by an assortment of flying buttresses and spires, creating a skeletal appearance which still echoes in modern glass and steel structures, the shape of the cloth is a function of the skin, the skin of the skull and eyes, and the head a function of the soul of the bust. Fundamentally, Spengler opposes the art form of the Classical and Western worlds on the grounds of act and portrait respectively, the former is pure surface and only intends to show a moment of an action (see Discobolus), whilst the latter attempts to capture the energy of a living soul, interior to exterior, will to body.

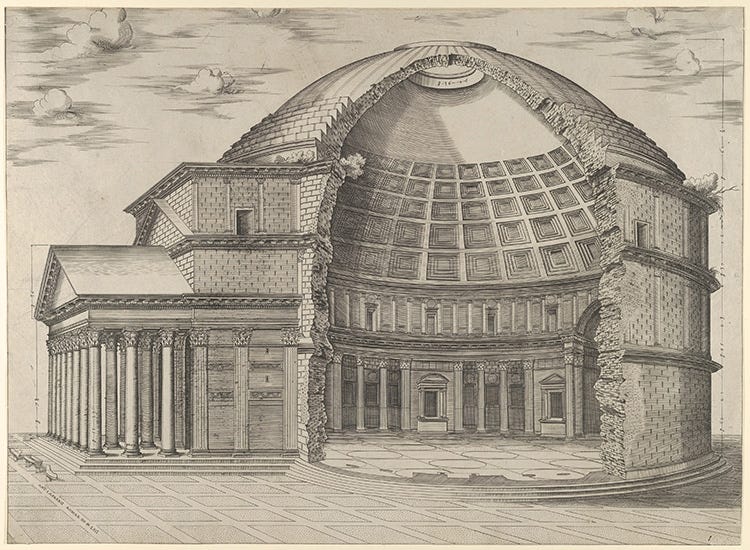

I mentioned in the previous post that a culture will elect the fine art that best expresses itself. Nowhere does this fact prove itself better than in the enigmatic Magian culture. There is no sculpture, no portrait painting, no frescoes and little to no musical tradition to be found in the Islamic “golden age”. Architecture, calligraphy and arabesque thrive by contrast. Anything material or external was denied sanctity, resulting in waves of Christian iconoclasm that ravaged the late Roman world in opposition to the dead Apollinian spirit. I’d recommend you take a view of the Wikipedia page for the list of Roman emperors; there you can scroll through all of Edward Gibbon’s volumes in 1 minute by just looking at the progression of imperial depictions as the Classical dies away and is replaced by the Magian spirit. The earliest Magian expression is Hadrian’s irises. Classical sculptures were painted and so never warranted carvings when their eyes were to be coloured separately, but Hadrian’s statue shows a different feeling budding in his soul, which would flower out into a Byzantine tradition of depicting their rulers with enormous, glaring, all-seeing eyes. What’s notable about Hadrian too is along with Trajan he commissioned Syrian architects such as Apollodorus of Damascus to construct various works in and beyond Rome. One such work, the Pantheon (below), was for Spengler “the earliest of all mosques” as Hadrian imported the young Magian great style to Rome for his own personal taste. The emphasis on the interior is apparent and abrasive against the peristasis of other Greco-Roman works. The Athenian Parthenon was designed to be witnessed from an exterior distance, evidenced by its inwardly angled columns and once-blue triglyph colouring that countered the illusion of crookedness and gave depth from afar. The Pantheon by contrast was to be viewed from the inside, the concrete dome was the first of its kind and crowned with an oculus to allow light to pour in from above into the open space. Needless to say, the structure is a metaphor for the Magian worldview: that reality is like a cavern, light, truth, creation, perfection, all things that are good, pour in from above, and make battle with dark, deceit, destruction, chaos, the counter concept of light - evil - residing below. The material world is an illusory production of this tension of light and dark substances, therefore the Pantheon, Christian basilicas, synagogues and mosques of this time, all begin and end with the interior, whilst the Classical temple begins and ends with the corporeal exterior, and the Faustian Cathedral begins with the interior and thrusts upwards and outwards.

How about Egypt and China? These cultures prove worldviews aren’t always about proximity, distance and physicality, they can also premise themselves on a journey. Their sculptures differ in this light.

“In Egypt the face of the statue was equivalent to the pylon (gate), the face of the temple-plan; it was a mighty emergence out of the stone-mass of the body, as we see in the “Hyksos Sphinx” of Tanis and the portrait of Amenemhet III. In China the face is like a landscape, full of wrinkles and little signs that mean something.”7

The Egyptian worldview saw the world as a straight narrow path from beginning to end. This is the meaning of their statues always being forward facing and regulated. The Pyramid, the sarcophagus, the sequentially columned hallway, all present an image of a culture that preserves life into the far future. Conversely, the Chinese worldview is the Way, garden art has always been a staple of this culture in reflection of the winding journey that takes you through life. “The temple is not a self-contained building but a lay-out, in which hills, water, trees, flowers, and stones in definite forms and dispositions are just as important as gates, walls, bridges and houses”8.

Egypt, China, and the West all exhibit a tendency or idea that is completely absent in the Greek worldview: energy. From Thales to Aristotle, potential energy is an idea fought viciously against. The many arche debates of the pre-Socratic philosophers concern how a substance - earth, fire, water, air - could have an inherent property of movement, so they could deny the notion of immaterial forces. For example, McKirahan, in Philosophy Before Socrates attributes Empedocles’ “Love” and “Strife”, described as substances, to an inability to conceive of immaterial forces in the 5th Century BC. Force reaches out, extending itself into space, it is also the far-reaching feudal officialdoms of Norman England, the Old Kingdom and the Chou dynasty, which sought to organise society on a mass scale towards the future. A symbol of energy, and movement is the notion of “care”. Care for your fellow man, because you care for their future. In art, this manifests in the depiction of children and motherhood.

“The child links past and future. In every art of human representation that has a claim to symbolic import, it signifies duration in the midst of phenomenal change, the endlessness of Life.”9

“Endless Becoming is comprehended in the idea of Motherhood, Woman as Mother is Time and is Destiny. Just as the mysterious act of depth-experience fashions, out of sensation, extension and world, so through motherhood the bodily man is made an individual member of this world, in which thereupon he has a Destiny. All symbols of Time and Distance are also symbols of maternity. Care is the root-feeling of future, and all care is motherly.”10

Mother and child symbolise the linking of generations through time. There is a staunch difference between imaginations of Mary as her maternal significance was raised in status between the Magian Byzantines and Faustian Europe. In the former, the “Theotokos” was venerated with golden halos, praised as the gateway between man and God. In the latter, she is the “Mater Dolorosa”, the “Mother of our Sorrows”. Between the two, Guido da Siena’s “Jesus Crucified” (above) shows a tragic aspect emerging out of his Byzantine inspired works. In the West, Mary takes on a tragic aspect in her depictions. Michelangelo’s Pieta (above), one of his earliest works at 23 years old, demonstrates the tragedy of the mother of God losing her son and having her continuity cut short. Care is a feeling that is not entirely visible. So when the Classical world presents its own accounts of womanhood, this lack of visibility manifests. The women of the Classical world were the upholders of the polis’s continuity, but continuity is foreign to Athens. There are no symbols of mother and child in Greece. Its equivalent of motherly destiny are the three fates, but there are no children to speak of. Aphrodite is a goddess of passion but not care, Praxiteles depicts her in the nude also, her form is complete without children. Women of the classical world were idealistically Amazons. More so, we understand that these depictions are soulless, there is no Mary equivalent because none of these women are engaged in character-specific conflicts. At best you get Helen, whose adultery tore a city down, or Medea, whose quest for vengeance was for the loss of a past lover, but not a lost future.

So far, we’ve used statue quite a lot to demonstrate how the cultural prime symbol takes primacy over any type of art. There is no art of statue, music or painting, only the infinite, the corporeal, the cavern, the narrow path and winding way. We will finish this post by taking a look at how cultures interact with other “fine arts” not as taking part in a development, but as a self-expression.

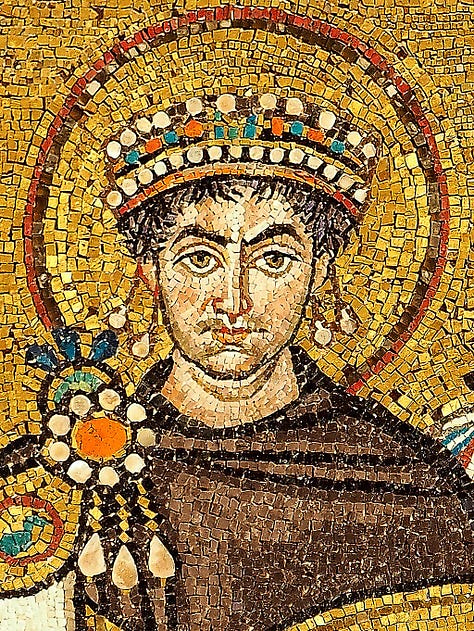

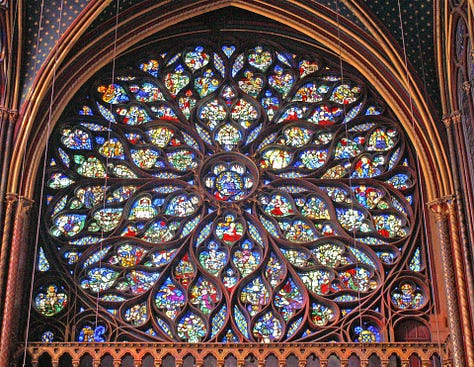

Take mosaic for example. Greek mosaic often consists of marble. A famous example of this is the Battle of Issus which gives us our iconic image of Alexander the Great. The colours consist entirely of reds, yellows, blacks and whites, abiding by a tetra-colour tradition that has its roots with Polyclitus and vase painting. In 547, Justinian I’s iconic mosaic panel was completed in the Basilica of San Vitale. This shows us a different and entirely unclassical idea, a golden background. Gold was rarely traditional in Greek mosaic or painting, but in Christian times it became standardized. Then, with a shift in time and place, a new type of mosaic arrives in Medieval Europe: Glass Mosaic. Purples, blues and greens became standardized in this mosaic, and the golden ceilings of the basilicas lost their significance. Is this a linear development in the advancement of mosaic art? We know now that such a notion is purely of a Western sensibility.

Marble is opaque and therefore needn’t grapple with inner qualities. A Greco-Roman mosaic is comparable to Democritus’ atoms forming together the world from its indivisible building blocks. Its tetracoloured style is the four elements, even fire of which was seen as corporeal in some shape or form. Much speculation into the potential colour-blindedness of the Greeks has been made, but the Greeks were perfectly aware of the effects of blues and greens, using them to create depth on their temples. But in the high style, on their painted sculpture, on their vases and mosaic and frescoes, there was an unspoken ban, because blue and green symbolise the heavens. Infinite skies, deep oceans, they are unsubstantial colours and purely atmospheric, which makes them perfect for glass mosaic, delimiting the biblical depictions from the Earth. But do not be deceived. This is not an opposition of Pagan and Christian. This is an opposition of infinite versus corporeal. Glass mosaic is a far cry from the golden backgrounds of Magian art.

“The Magian felt all happening as an expression of mysterious powers that filled the world-cavern with their spiritual substance — and it shut off the depicted scene with a gold background, that is, by something that stood beyond and outside all nature-colours.”11

Gold is not a colour. The metallic quality of it creates an almost magical impression as against yellow, and is apt for imagining the eternal presence of a holy spirit that contains all creation. But the lesson of the Cavern-idea is that one must submit to God, which found its epitome in Islam, whilst the lesson of the Infinity-idea is that the ego must affirm itself before God, breaking all limitations until it gets there. Glass mosaic is not merely to serve a double function of allowing light into a church and telling biblical stories in pictorial form, it is an ornamental expression of Western culture’s limitation-breaking nature.

Glass mosaic naturally implies the use of windows. Very rarely do holy sites have windows except in the West where they are a central component. Egyptian temples have no windows, Greek temples have no windows, their interiors occasionally opened to the sky, mosques occasionally had windows but they were often concealed by galleries, and then Europe going on from the Middle Ages becomes “more glass than wall”. The space between interior and exterior is once again opened up to one singular expanse.

The point of this post is to open your mind to the way in which Spengler defines and describes cultural differences. The next post will begin to look at how cultural art first makes an appearance in the high cultures.

The Decline of the West Vol.1, 1918, p.200.

Ibid., p.202.

Ibid., p.200.

Ibid., p.261.

Monism – A very difficult but elegant 6th Century philosophy that, simply put, denies extension spatially or temporally as merely illusory. There is only what is (presence) as what is not (distance, past, and future) is not.

I am aware that Hellenistic works like Laocoon and the Terme Boxer showcase far more emotionally vivid works, but these exist outside of the culture period. This is not a cop-out to avoid addressing them, art in the Civilisation period loses its strict form-language as it successively creates simulacra of itself. Winckelmann, who first categorised the tripartite Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic development, identified it as excessive and overdone, something key was lost in their production.

Ibid., p.262.

Ibid., p.190.

Ibid., pp.166-167.

Ibid., p.167.

Ibid., pp.247-248.