The previous post established Spengler’s idea of the “great style”. It is the expressed character of the culture from its beginning to end and contains subtle and subconscious symbolism which allows us to identify it. The idea of the great style refutes history’s continuous nature; the nature of the pyramids is not on the same timeline as the mosque or the skyscraper. Instead, cultures express and explore one fundamental and underlying idea to its maximum and use material and technique as sentence and grammar to tell that meaning.

We’ll recap the cultures in question. There is the Apollinian (1100 – 350 BC), the Greco Roman culture whose prime symbol is the self-contained body. There is the Faustian (900 – 1800 AD), the West European culture whose prime symbol is infinite, disembodied, space. The Magian culture (0 – 800 AD) resides in the middle east and is premised on the idea of the Cavern, within which substantial notions of light and darkness are in push and pull. The Egyptian (2900 – 1700 BC) sees life as a forward march from birth to death, whilst the Chinese (1300 – 440 BC) sees it as a winding path, twisting and turning through nature before reaching its destination.

This post will dissect examples of how the great style manifests in the “early period” of culture. Before we can dive into this, however, I want to continue off of What is Art? to refine our understanding of Imitation and Ornamental art, which I have previously corresponded to “Resonation” and “Symbolism”.

The general act of imitating, copying, has a religious significance to it. Self-recognition comes with the opposite recognition of the alien, what is not ourselves. I don’t speak of another equal, like another person or animal or differentiated phenomenon we’ve chosen to give a name to, but the whole universe itself. This is the opposition of Microcosm and Macrocosm. Religion treats this as the opposition of ego and God and the goal of religion is to bridge our individual, differentiated souls with the all-encompassing soul of God. Imitation is exactly this but stripped of fancy language. Imitation is resonation because when the I and the Thou vibrate as one, they become one.

Of course, I don’t literally mean shaking up and down like a moron, but frequency and pulse is a quality of the plant-world. Plants resonate with the four seasons, the daylight cycle and their own lifespan, pulsing in and out. Imitation is an act of foregoing independence of thought as you “let yourself go”. It could be going to sleep, dancing to music or marching in lock-step, but you forego a part of yourself to join a higher form. But you can only imitate that which is living. Imitation requires a feeling, or energy that can hold itself together, the dead have no such energy, no pulse, no motion, no vibration. Motion is a quality of Time and therefore Imitation belongs to this aspect.

Ornament does not. Ornament, and if I capitalise the word then I mean it in the Spenglerian way, doesn’t vibrate, resonate, it doesn’t channel energy but stands rigidly against it. If Imitation is the foregoing of a part of consciousness to be part of a larger movement, Ornament is the affirmation of self-awareness against the chaotic comings and goings packaged in with Time. This is Religion’s other motive. The natural world is filled with daemonic energies, chaos and unknowns. Our natural fear of the unknown pushes us to bring things into the light of our awareness, but in so doing it is given rigidity as part of a system. The cosmic flowing of Time is crystalized into perfect and unchanging Space in order for us to understand it.

Art is a technique. Strict arts are composed of a grammar and syntax, rules and laws, logic and tradition, which give communicative value to what would otherwise be a purely self-satisfying expression. These rules are products of Ornamental symbolism and they produce Ornamental art. A tendency emerges here that Imitation itself will likely emerge in what is living, whilst Ornament will emerge in what is dead.

“And now for the first time we can see the opposition between these two sides of every art in all its depth. Imitation spiritualizes and quickens, ornament enchants and kills. The one becomes, the other is. And therefore the one is allied to love and, above all — in songs and riot and dance — to the sexual love, which turns existence to face the future; and the other to care of the past, to recollection and to the funerary.”[1]

The peasant’s cottage and the lords castle both represent the living and therefore imitative technique and art. The style of the peasant’s home is always a function of the materials his land has access to, what the peasants father left him when he inherited it and what little he will maintain and leave for his son. The plan of the castle is always purposed to defence. Imitation here breeds a form from a whole history of mistakes and blunders. It doesn’t stop to theorize, it simply defends by experience in-the-now. These are the places that art is made because this is where people actually live. But only the gods live in their holy temples. A cathedral or a temple or a mosque is a site of strict rules and regulations because it is art unto itself. The accompanying monasteries are homes to learning and thinking in the abstract through strict rules and laws to communicate precise meanings, because precision of word and deed is the only means to subjugate the daemonic, hence why demons are defeated when you call out their true name. A castle’s walls may ebb and flow in and around the geography of its defensive position, disorganised on the surface but perfectly adapted to its position, but holy architecture is built in symmetry, proportion, delicateness, denying the landscape it resides on. Equally, another useful point of observation, as we shall see, are tombs in whatever form they come in. How a culture treats its dead plays into its artistic techniques as well.

I raise this for a simple reason. Art in the early period is a. Architecture and b. deeply ornamental. The feeling of a common culture and prime-symbol begins as a wide and ill-defined sentiment before crystalizing over centuries into refined forms. Medieval art hadn’t quite reached the refinement of oil-painting and orchestral music quite yet, its early style is simple and operates in 3-dimensions as an architecture, and ornament in particular can only express awareness against nature, and calcify the symbolism of its worldview, in holy architecture, which is purely made for the good of itself. A castle type will only tell us the strength of the people’s form of organisation, but a temple-type will tell us the character of that form which is what we are after.

I will divine this into three parts. First, I will analyse of the pre-cultural period to identify symptoms of the high culture’s emergence, second, I will look at the universal features of the early period, and third, I will explain how each culture I cover expresses its unique character. The early period of the Egyptian world spans from 2900-2400 BC, but I will be using examples from other periods as well, the early period of the Greeks spans from 1100 – 650 BC, for the Magian its 0 – 500 AD and for the Faustian its 900 – 1500 AD.

The pre-culture is more or less defined in art terms by its incoherency of consistent style. The Carolingian period[2] Spengler identifies as “between styles” and lacking a coherent ground plan. He cites for us the Church of St. Germigny des Pres (c.800) as baring more hallmarks of an eastern style, such as horseshoe arches and byzantine golden apses than, say, the Romanesque style of the middle ages. There are no traces of a budding Gothic. This doesn’t necessarily go for Aachen Cathedral, constructed by Charlemagne and consecrated in 805. This structure does look Gothic, but only on the exterior. The Palatine Chapel, the oldest part of the structure, was designed by the Armenian Odo of Metz and was modelled after the Byzantine flavoured Basilica of San Vitale (c. 547 AD) of Ravenna. Its Gothic exterior is a product of later works as it became a go-to spot for the coronation of German kings. Carolingian architecture is demonstrably influenced by another culture’s style possessing none of its own.

Mycenaean[3] architecture is difficult to pin down as most of it has not survived the eons. A notable example of Mycenaean works is the “Lions gate” at the Mycenae site. It is constructed in cyclopean masonry which was developed, not by any one place in the Aegean Sea, but was emergent as Mycenaean, Hittite and Minoan regions learned from one another. The Lions Gate in particular was raised likely in response to a wave of attacks pre-empting the downfall of the culture, meaning its use was defensive rather than expressive. The hulking style of these walls are contrasted with more delicate styles reminiscent of future Greek interiors, featuring columns and fresco-painted walls. Their Tholos tombs, otherwise known as beehive tombs, have entrances cut into hills, not too dissimilar to many of the Egyptian tombs found in the Valley of Kings. It’s unlikely that the Mycenaeans had direct access to Egyptian sites, but Cnossos was likely a sort of late-stage civilisational melting pot due to its maritime trade. They have tombs of their own which seem to mimic Egyptian rock-cut tombs, explaining why Mycenaeans used this type of tomb technique. These two examples illustrate an emergent style that is not symbolic of anything higher but simply copied from the past and given a native air.

Magian pre-culture I will keep short. There is a world of difference between the Second Temple of King Herod and Al Aqsa Mosque. The Dome of the Rock shows a ripe, strong and pure sense of the world whilst the Second Temple, which once stood in its place, is a Carolingian style mimic of Classical architecture. When we look at a piece of art, especially architecture which has no moment of cancellation or beginning like this or that genre of fine art, it’s integral to discern whether it is expressing a sense of self, or it is imitating something from another time or place. Both can be prevalent at the same time. Though Spengler actually says this cannot be the case particularly in the early period, he means to say the symbolism of one culture cannot mix with another. The basilica type of late antiquity is fundamental to the cross-shaped cathedral style, but it was given a different form of symbolism and adapted to that purpose henceforth.

The “Early period” is a very large stretch of time to surmise as simply “architecture”. Specifically what Spengler attributes to the early, or Spring, period is architecture and decoration as the two main types of Ornament. However, the trend to be observed, which continues into the Late period as well, is that architecture begins as the primary form of expression, before decoration and secondary symbols seep in that go on to become the genres of fine art for the late period. It can be reasoned, as I’ve said, that architecture has always been part of society, due to the function it serves, but we must also remember that holy sites are not functional in the way a home or a castle or a work-place is. These structures are built for themselves only. They are pure expression and so there is reason in how these structures present themselves with or without decoration.

There’s no better example of how architecture starts out as the primary form than the Giza Pyramids. These are tombs, so not necessarily religious sites, but nevertheless there to bury their Gods. The tombs of Khufu and Khafre, with their casing stones, would have been a monumental resistance to nature, a mathematically perfect pyramid jutting out of the desert in defiance. The symbolism was expressed purely through the surfaces and edges of the structure and decorations to it would only have taken away from its grandeur. It’s something perfect and immovable in an ever-changing desert. Like all Ornamentation, it is the epitome of killing the natural world, the world of time, and replacing it with something purely spatial. I find it amusing that we, five thousand years on, try to give these monuments some kind of conspiratorial functionality, when all the mathematical precision we find in the angles, surfaces, and its geological positioning, are a product of a religious passion to express symbolism rather than a scientific desire to harness energy.

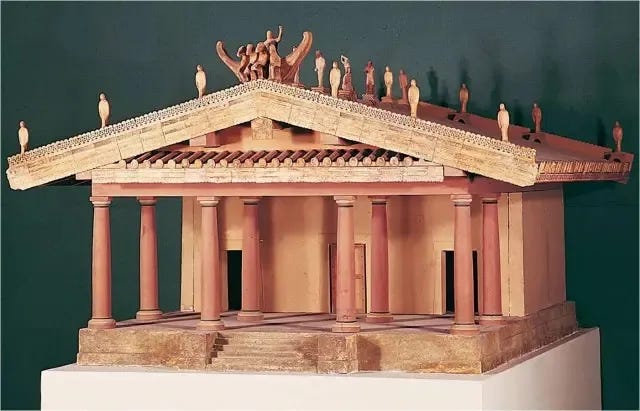

The pyramids were built from limestone blocks. Stone for early cultures has always been the go-to resource for building architecture. Stone is permanent and unmoving. Perfect for its use in structures that are meant to be artistic meaning. Despite this, there’s an exception. The early period of the Greeks, that is, 1100 to 650 BC, encompasses the exact time-frame in which the iconic Doric temples of Greece were not in use. In fact, Spengler’s decision to mark Greece’s late period as beginning here is no inconvenience to him; these temples accompany the timeframe in which sculpture began to make headway in Greece as well, making both a product of late-period art forms. The equivalent to the pyramids and early cathedrals in Greece was the complete negation of architecture outright. The “Templum”, or “Temenos”, was a zone created with markers temporarily for the practise of rituals. It would then be disbanded promptly afterwards. These were generally popular in the early centuries leading up to the Archaic. After around 700 BC, we see a shift towards wood as a construction material for “cabin temples” as Spengler puts it. It’s not like Greece was unable to build in stone, they at the very least used mudbrick as evidenced in the structure of these early temples, rather what the use of wood signified is the same idea as the temporary Temenoi: presence. The Geometric Greeks gave no concern to creating permanent structures in the same regard as their oldest philosophy is only from the 6th Century. Stone represents an endurance, the permanence of Truth, and wood decays and leaves nothing behind in a relativistic short amount of time. Maybe if they built in stone, we’d have some trace of their existence in this period, but then they’d be committing a sin they didn’t even know they were avoiding. Additionally, stone allows a 3-Dimensional logic to express itself as architecture, the absence of stone in Greek Temenoi isn’t the absence of symbolic meaning, the absence is the meaning for a culture that denied spatial or temporal extension.

Now the Magian culture is a difficult one to pin down. This is because they don’t possess their own pure architectural style. This is because their spirit and ability to express it is suppressed by the dominance of the aged and final forms of Roman art and Architecture. As a result, Magian architecture is forced to express itself using a foreign stock of forms. This, Spengler calls the pseudomorphosis.

Notable examples of this pseudomorphosis come mainly from one singular architect: Apollodorus of Damascus. He was commissioned in the early second century by Trajan and Hadrian to design various projects in the centre of Rome. The Basilica Ulpia and Trajan’s Forum are directly associated with him and the Pantheon is speculated to belong to his genius as well. In this period there are distinct but subtle shifts in Roman architecture as a whole. The Ulpia featured two apses (example above) on either end of it. These rounded sections are alien to classical sensibilities. Its especially alien considering Basilicas originally were never religious sites they were judicial and business centres and gained popularity when the empire Christianised as sites for mass when large roofed structures were needed to house large crowds. Then there is the Pantheon. It is seemingly a Roman design only it has a few unusual features. The most obvious one is the Dome. It is hollowed out with coffers and creates an enormous open interior space where the vast bulk of decoration lies. On the exterior, the outer walls are flat and undecorated. These walls may buttress the interior dome, but there is no reason to not give them a Roman appearance on the outside too when historically the exterior has always been the focus of classical temples. The dome is crowned with an opening, an oculus, which allows light to pour in from above into the otherwise windowless space.

If I were to describe a domed structure with rich interiors but little emphasis on the exterior, I’d be more inclined to think of any mosque on the planet before a classical structure. This led Spengler to identify the Pantheon as the “first of all mosques” in lieu of it embodying the Magian worldview more than the classical. Lastly, we must look at Hadrian’s villa in Tivoli. The Greeks placed a special emphasis on the post-and-lintel style of column and architrave. It was not challenged until the second century when suddenly we see arches spring from the columns themselves. Until then, there were arcades in the form of walls featuring arches within them, such as the Colosseum, theatre of Marcellus and various aqueducts. But never arcades of this type. All this illustrates the permeation of a new artistic emphasis on Roman life which would only strengthen in the following two centuries into something so thoroughly alien to classical architecture, one should question whether it was merely the ideas of Christianity behind such a transition when the Hagia Sophia (c.360) was raised over Constantinople.

Lastly, there is the West. Charlemagne moved to imitate Byzantine motives, literally straight up copying their works. But with Otto the Great (c.912 – 973 AD) in Germany, a new wave emerged. Architecture returns to triumph over decoration at St Cyriakus and Panteleon. This “Ottonian” style gave way to the arrival of Romanesque which spanned Europe from Pisa to Durham. After the Normans conquered England, their own type of Romanesque became standardised for early Cathedrals. Although these works aren’t as blunt as a pyramid, they express the same purity of spirituality. The focus is on the shape of the building, which features very little, if any, decorative Ornament.

However, just like the transition from Templum to Temple, and Pantheon to Hagia Sophia, Western cathedrals feel an ornamental shift around the 3rd – 4th century of the early period. Ottonian architecture spans from the mid-10th to the mid-11th century, Romanesque’s dominance from the 10th to the 13th, and Gothic from the late 12th to the 16th. The end of the Romanesque proper marks the end of pure architecture as a mode of symbolic expression for Faustian culture. The 3rd century of the early period also begins the political shift towards the subjugation of the King to the Nobility (such as the Magna Carta), and therefore the State to the feudal Estates, and also reigns in a spiritual ripening through scholastic philosophy in 13th century Europe and 3rd century Rome. In correspondence, architecture begins to decorate itself. Compare the aforementioned bishop seats with Amiens, Cologne, Riems which are all in High Gothic. English cathedrals in the 13th century began to be constructed in the helpfully named “Decorated Gothic” such as Lichfield and Salisbury, whose facades, as in High Gothic style, begin to feature series of statues in niches and columns. This is also the period we get Sainte Chapelle, Paris, with its impressive window mosaics. The movement from architecture to decoration is the point where the culture begins to select its chosen techniques for artistic expression.

In Rome, you had the spiritual embryos of both the Mosque and Cathedral. Byzantium opted to prefer the Pantheon and domes became its signature icon. In the time of Otto the Great, basilicas were chosen instead and the cathedral transformed the building type into something of its own… Why? Why couldn’t the West just adopt Byzantine architecture since it clearly already had it? Why did they need to create a whole new language to express Christianity through art and architecture when Byzantium had already spent 800 years establishing that for us? Why were domes not popular in Europe? The answer to this lies in what religious architecture is fundamentally.

Holy architecture is meant to express the macrocosm in its purest form. The house of God is a microcosm for this macrocosm allowing man to engage closer with the divine. The whole of the Magian style, from its apses, to its domes, to the arches that spring out of the arcade columns, signify a leaping up and then a rounding off of the enclosed material world. Gothic architecture had not a shred of this motif. Its arches are pointed instead of semicircular, allowing for the support of heavy vertical loads. Its walls are hollowed out, filled with glass and lightening the load of the overall structure to the same end. Instead of minarets, it has hegemonic bell towers, and instead of domes it has spires, and even Florence Cathedral’s central dome was pointed. These structures were often so large they could contain the whole of their respective cities in their day. For the Magian Christian, the outside was closed off, for the Faustian Christian, it was thrusted into. Lincoln Cathedral was the tallest structure in the world before its spire was dismantled. The Christianity of northern Europe was resolutely opposed to the Christianity of the middle-east as it sought to expand to the furthest reaches it could.

This is why analysing the symbolism of a culture is so important. It draws out the indefinite from the definitive. There is the tool and the user, the language and the race that speaks it. Christianity has been there at the Spring of two cultures and has manifested in two different ways. Budding in Russia is even a third as seen in the onion domes of their churches. It demonstrates that the same book, the bible in this case, can be interpreted, not merely in a relativistic manner from individual to individual, but can generate whole different spiritual receptions towards its significance as well. So now we will look at the symbolism of their respective macrocosms.

Bells reverberated across the plains and forests of Europe. Organ music, despite not being, like the choirs and psalms, strictly a Faustian addition, would fill every crevasse of the interior with sound. In the 12th century, counterpoint[4] would then be invented bringing with it a new air to the discipline of sound. Music is the ultimate form of disembodied radiating space. Hence, in the Baroque, orchestral music would progress to become the central art-form of Faustian culture. As has been illustrated previously, the cathedral also embodies within it the function. The enormous interior would push itself apart as the pointed vaulting leans against the walls over time. This is why the Hagia Sophia has traditional buttresses that lean against the wall, but the flying buttress has the two-fold task of airing out the exterior so sunlight can reach the windows without being blocked. The solution was the flying buttress which floats between the columns redirecting tension downwards. The effect this has on the architecture is almost a skeletal appearance like a ribcage. This bare-bones, foundational look, illustrating the functionality of the architecture, has since gone on to become a staple of all Western structures to this day, particularly the glass and steel skyscrapers which are symbolically cathedrals for the Third Estate. Speaking of glass, the light-permeated window art, which is exclusively an art of West-Europe and nowhere else, serves the same premise as the flying buttress supporting the nave and the music of the bells and organs. A cathedral’s motive is to begin in the middle and thrust outwards. It is the product of a feudal time wherein the papacy sought to bring the whole world under its dominion in a single feudal vassalage. It is the product of a cosmic worldview that pits the woman cloaked in starlight against the dragon in Revelation 12, an unfathomably large, austere, universe filled with cosmic scale wills and forces for which in the face of it we are so dwarfed. It’s not enough for the cathedral to be wholly self-contained in a discipline of strict customs and proportion like the Greek temple, it needs to subdue the world under its logic in order to acquire God’s attention. That is the fear of the unknown that has driven our sciences, arts, and political ambitions ever since.

The pointed and rounded arcades of the Christian cultures are opposed by the post-and-lintel columns of the pagan, which is to say, the Apollinian and Egyptian. The trouble with this is that, as said before, Doric temples aren’t exactly “early” to the Greeks, and nor are Egyptian temples, as our best preserved sites are from the New Kingdom over a thousand year after the pyramids and therefore a product of the Civilisation period. But they provide an interesting contrast that is, at the very least, thoroughly religious, and when the next post is squarely concerned with the Renaissance, and after that the late period, there’s not really a better opportunity than now to discuss it.

Consider the temple of Rameses III, or the temple of Isis at Philae. These Sphinx-like structures are rectangular in shape and consist of sets of courtyards and hallways before one reaches the inner sanctuary. They are enormous hallways. The columns are all on the inside of the temple and their capitals expand and flower out to support the ceiling posts whilst their sheer mass comes to block off the side-views. The Doric temple, by contrast, takes the motive and turns it “inside out like a glove”[5]. With all things Apollinian, we are faced at once with the reversal of motives on either end of its culture. The Greek took the Egyptian temple, as he took their statues, and restructured it so that the interior is symbolically denied. Then, on the opposite end of their civilisation, the Magian re-instils the interior with a new significance.

I think I’ve said quite enough on this matter. I recognise that architecture wasn’t alone in any culture, but it is the first mode of expression for the new-born culture and there is much to extrapolate from it. Topics like the Pseudomorphosis would have their own departments of historical study if Spengler were more appreciated, so I can only delve as far as I reasonably can without publishing a book of my own. But what we see here, overall, tracks with everything else you will have noticed about the early period. Religion is split into an early-early period and a late-early period along the likes of new-born sentiment and refined scholasticism, at the same time, politics in the west goes from world-spanning feudal hierarchies to devolved estates dominating the state-structure. In the 12th century this shift occurs, and Romanesque dies and is replaced with high-gothic. The same rough developments are present in other cultures, which only makes sense even from a non-Spenglerian view as shifting intellectual attitudes and power dynamics demand a new wave of cultural production.

Pure architecture in the first few centuries reflects the new-found feeling of the culture. Stone expresses the macrocosm in simple, geometrical terms. The feeling for God hasn’t been picked apart yet, so nor has its architecture. Then, after three or four centuries, architecture gives way to symbolic decoration. The feeling for God is being explored and systematised, and so like branches and sticks and leaves these holy structures become more and more ornamented.

The next post will address how the Renaissance was NOT a revival of the classical soul, but a reception of it by the late Faustian Spring period.

[1] The Decline of the West Vol.1, 1918, p.194.

[2] A period in West Europe between 700 and 900 AD. Associated with Emperor Charlemagne (748 – 814 AD).

[3] The pre-cultural period of the Apollinian. It spans from 1750 to 1050BC in three stages.

[4] Two coinciding lines of music in relation to one another.

[5] p.198.